If you haven’t noticed, I’m a big supporter and advocate of my Tennessee State Parks! I recently wrote an article on Memphis-area state parks and had the great fortune of chatting with Hobart Akin, the parks’ Cultural Resources and Exhibits Specialist. The piece was a guide to Meeman-Shelby Forest and T. O. Fuller State Parks, the two state parks within Memphis city limits, but it was the stories of their pasts that really caught my attention; both were deeply influenced by the racial history of the south. In the segregated era of Jim Crow, Meeman-Shelby Forest was the park for whites, while T. O. Fuller was for Blacks.

Mr. Akin recommended a book that explores this lesser-known part of recreation history, William E. O’Brien’s Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South. I immediately requested it through InterLibrary Loan and found myself engrossed in this story that is way under-told!

Here’s the quick summary…

In the first quarter of the 20th century, the National Park Service, faced with increasing requests to preserve lands as national parks, began a campaign to expand conservation and recreation areas to a state level. This way, states would have “competent” agencies to preserve landscapes that, while perhaps not of the same “outstanding character” as national parks, would follow the same high management standards. In 1921, the National Conference on State Parks convened in Des Moines, IA, and established a goal that there be a state park within a 50-mile drive of every American.

But while the state parks were envisioned along the same egalitarian lines of national parks – as a symbol of democracy that provided restorative access to nature to all citizens – the achievement of this federal ideal was left, in practice, to state level decision-makers. And when Jim Crow laws ruled southern society, equality was never a priority.

Concurrently, the criteria of what should constitute a state park was a loose, debatable definition. One argument was that state parks should be preserved sites of “distinct and notable” landscape, while another viewed state parks as recreation opportunities. The latter definition was often embraced to justify continued exclusion of African Americans from public spaces: in a “separate but equal” world, the better landscapes and facilities were open only to white visitors, while Blacks were relegated to the inferior spaces of picnic grounds and day-use areas (often under the stereotyping belief that “they wouldn’t use them anyway”).

So what happened?

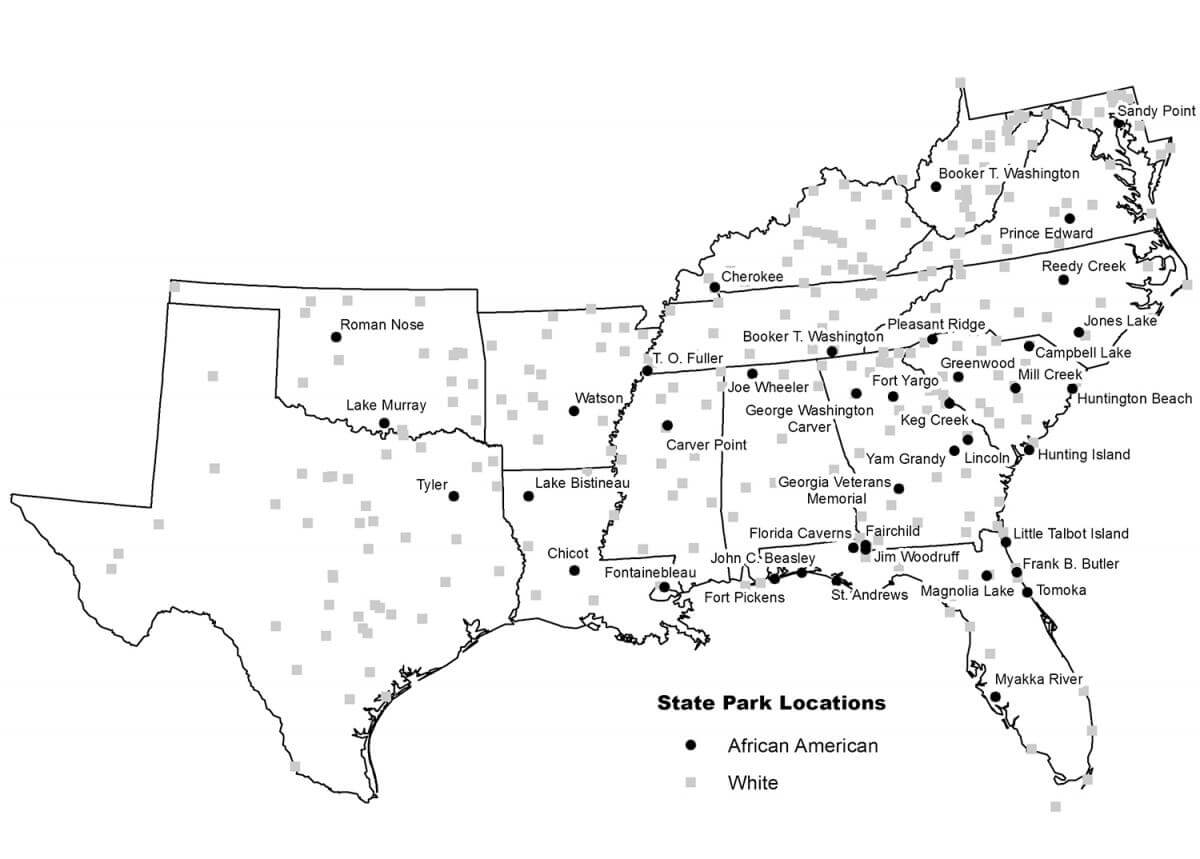

This continued for decades as state park systems developed and designated new park areas. While there was some recognition of the need for African American access to park spaces, it was never made a priority. There was always one excuse or another that prevented the development of parks specifically for Black visitors, despite the massive growth in state park numbers, in general, from the CCC and WPA projects of the New Deal. The result was a vast difference in the number of state parks accessible to Blacks and whites in the first half of the 20th century. As the New Deal era expired and WWII arrived, park growth remained fairly stagnant, still excluding people of color and with no plans or promise to change that.

After WWII, though, the angle of Civil Rights shifted from one that desired access (despite “separate but equal”) into one of full integration. After all, African American soldiers had just risked their lives overseas in the name of democracy – weren’t they due those same ideals at home? The integration movement terrified these southern states and suddenly many of them decided that they better build some facilities for African Americans. But separate facilities were no longer enough, and the demand for integrated access increased. For years, states grappled with indecision, public debate, and lawsuits from the NAACP; some even stubbornly closed park access entirely rather than embrace integration. All park systems were officially integrated by the end of the 1960s, often quietly and without the pandemonium that was feared, but these decades of exclusion have had a lingering impact.

The impact today…

According to a 2018 survey by the National Park Service, less than 1% of visitors to National Parks are Black. To blame this statistic on assumptions or stereotypes is misguided and excludes a major part of the story. Without the context, our understanding is limited; a lack of awareness prevents the knowledge necessary to effect change.

O’Brien concludes with a look at these spaces today. Some have been reverted back to private land; some have been downgraded to city or local park systems; ones that were once designated as “Negro areas” have simply been absorbed into the larger park; a handful remain just as they were. What’s missing on a whole, though, is the recognition of this history. With a few exceptions, there’s hardly any signage or storytelling in these spaces, meaning this history could be unknown to even their most frequent users.

If you’re a supporter and patron of your local outdoor spaces, I hope you’ll consider this history the next time you enjoy the great outdoors.